Complex Dynamics

Mathematician Dr. Robert D. Ogden reflects on being an Anglo in Anglican Hispanic ministry

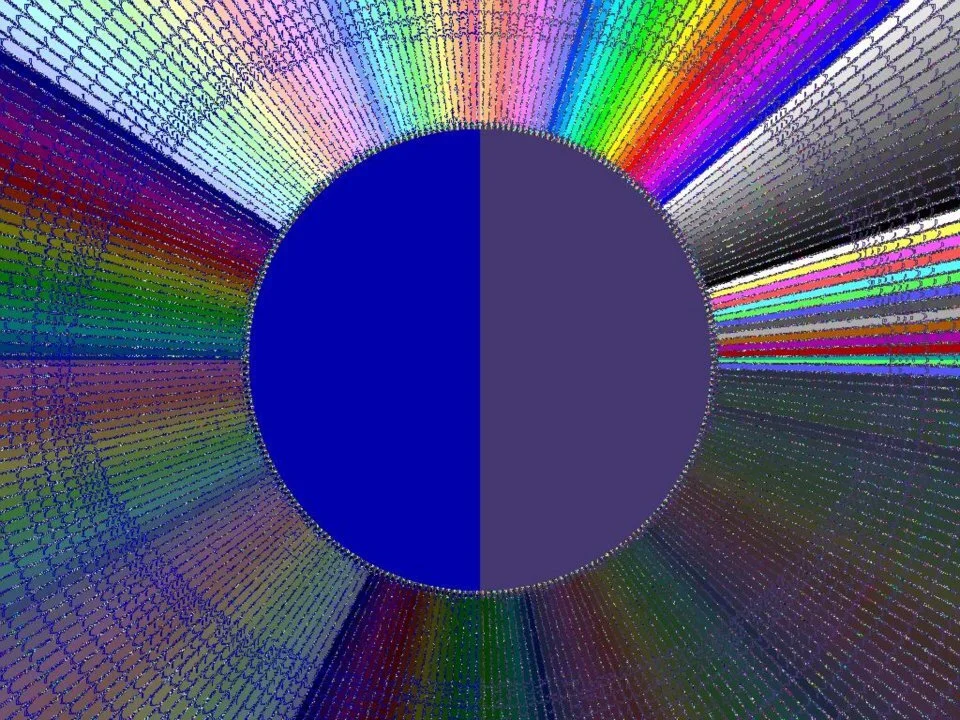

“BWHEARTS” (2011) fractal art by Robert D. Ogden

Complex dynamics

the study of mathematical models and dynamical systems defined by iteration of functions on complex number spaces

Fractal created by recursively growing a cross at each of its four line ends as many times as desired. Source: Andy Long’s Classes

Fractal

a never-ending, infinitely complex pattern that is self-similar across different scales; created by repeating a simple process over and over in an ongoing feedback loop

Before I retired, I used to teach the mathematics behind the fractal images that illustrate this article.*

The students were graduate students in computer science, and they were much more interested in the programming techniques than in the math. They would often ask me, “What's the math good for?” And I would answer, “The math prepares you for life.” They would scoff. To them, the somewhat abstract math in their educational experience was the furtherest thing from “real life” (whatever that is).

I explained that, in math, you know all the rules, and in the case of these fractal images, the rules are simple. There are no surprising inputs, and the program does exactly what you tell it to--yet, you still cannot predict what the image will look like until you run the program, and zoom in and see.

In “real life,” the rules are not specified precisely; unforeseen inputs constantly surprise you, and you usually can't zoom in for a clear picture. “So be humble, and accept the uncertainties of real life, because there are unknowns in even the most precisely specified entities of human creation.”

And thus it was with my Hispanic ministry at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Texas.

* Strictly speaking, my fractal images were not produced by a complex dynamical system of the iterated function type (except maybe the last one, "SHARE8") mentioned in this article—they were produced analogous to the famous Mandelbrot set. The idea is to define a simple function that depends on a parameter,c . For the Mandelbrot set it is fc(z) = z2 - c. Then one fixes z at 0 and allows c to vary, yielding the points 0, fc(0), fc( fc(0)), .. and sees where the sequence goes in the complex plane. A simple iterated function sequence would fix c and look at the sequence as z varies: z, fc(z), fc( fc(z)),...

In the Mandelbrot and related cases, the sequence for a given value of c can: 1) stay bounded or 2) wander off to infinity. The values of c (in the complex plane) for which the sequence is bounded are colored one color—say, black—and the ones that wander to infinity are colored with a color proportional to the number of steps it takes before you're sure it's a wanderer; then you choose a new value for c and start again.

The interesting phenomena happens on the boundary between the bounded and the wanderers: The set is complicated mathematically; it is typically not a curve and, depending on how you define 'dimension,' it has a fractional dimension, like 1 ⅓—hence the name fractal.

I made these images using an early version of the freeware program Fractint, which lets you specify the function and zoom in on interesting regions of the boundary, and then it redraws that portion. I spent hours running this program and looking at the cool creations that came up. Then I named them according to what they looked like to me.

“SPINE1” (2011) fractal art by Robert D. Ogden

Iteration of functions

the process of repeatedly applying the same function within the same function

Sometime around 1985, I was asked by my parish priest to be in charge of Hispanic ministry and to be the catechist for those who were more comfortable in Spanish.

At the time, I was a mathematics professor at a Texas university who—after years of apostasy—had had a conversion experience five years prior and renewed my confirmation vows in the Episcopal Church of my teen years.

My only qualifications to serve a Hispanic ministry were an interest in sharing church with Latinx friends and that I was reasonably fluent in Spanish after living and working in Mexico, from 1978 to 1980, though I still had a notable gringo accent. My friends and my compadres all called me, well, Roberto.

For some years, I organized Sunday services in Spanish. We used the Liturgy of the Word from El libro de oración común—The Book of Common Prayer—concluding with the Lord's Prayer and the Peace; once a month, we had a full Eucharist—the bread and wine, with a Spanish-speaking priest when we could get one. Usually, I also played the music (guitar!) and loved leading the hymns in Spanish, especially “Alabaré” and “Pescador de hombres.”

“THORN2” (2011) fractal art by Robert D. Ogden

Complex number space

mathematical space based on the number of the form a + bi, where a and b are real numbers, and i is an indeterminate

I was assisted in my ministry by La Familia Martínez, an interesting family with roots in Puerto Rico. They were our most faithful attendees, serving as lectors and acolytes at Mass. To them, La Iglesia Episcopal was the church of the poor and socially marginal, while the Roman Catholic Church attracted the well-to-do and socially respectable. (Although not the richest church in our small college town, our parish did consist mainly of white people in the professions, in business, or connected with the University.)

Another pillar of our little community was Marta Knabe. She was an aunt of Señora Martínez and married to a quite conservative Anglo who was very anti-clerical. He never attended church, and I don't think I ever met the man. But Marta had a lot of energy and enthusiasm for our mission. Though she would have been the logical person to run the Hispanic Ministry, she seemed to think a man had to be in charge; in fact, I believe she was the daughter of a bishop back in Puerto Rico.

Marta organized most of our outreach activities. One of the most ongoing and successful—for a while, anyway—were our celebrations of the visit of Los Tres Reyes Magos, around January 6th, the day children get presents from the Wise Men instead of on Christmas throughout Spain, Puerto Rico, and much of Hispanic America (although the commercial attraction of Santa Claus seems to be replacing or superseding this lovely custom). Marta would round up relatively needy children, along with their parents (usually the mother or abuela), mainly of Tejano origin, and get the Anglo congregation to donate presents or money therefor. Although Día De Los Reyes Magos isn't celebrated much in northern Mexico and Texas, the children loved it! Marta would find out the names of the children in advance so that each child would have a personalized present. The Martínez men (and later on my future godsons, Jessica’s brothers) would dress up as the Three Kings in special handmade robes; the daughter would dress up as La Virgen María. The Reyes would pass out the presents, calling each child attending by name. Then we would feast on enchiladas and good, homemade, Puerto Rican-style meatballs.

Everyone had such a good time, and it was so cool to get a present after Christmas with your name on it, that other children in the parish wanted to take part in the tradition, too. But these children were neither Hispanic nor “needy;” their parents certainly wouldn't say so. There was also a feeling by some that it was wrong to set the Latinx children apart. The parish’s attempts to deal with this seemingly minor issue uncovered some major contradictions in our program.

Some considered it selfish for the Anglo children to also want presents on Los Reyes, especially after what for many of them had already been a lavish Christmas (relatively, of course). Their parents came up with a solution: they would buy and label gifts for their own children and add them to the Wise Men’s gift pile. But the kids, being wise themselves, soon figured out that their parents had purchased the gifts, often with the intent of alleviating their children's post-Christmas disappointment. Ironically, this “inclusion” made the presents less a gift of the church community. The food and the songs weren't popular with Anglo members of the congregation, either.

“NEWT256” (2011) fractal art by Robert D. Ogden

Another focus of my ministry was my goddaughter Jessica's extended family. When my wife Rosie and I became her godparents, I had high hopes of this being an important shared ministry for us as a couple. Rosie is Roman Catholic, and at the time, ecumenicism was in the air—there was hope that Anglicans and Roman Catholics might even share Communion in a few years. In fact, I rashly predicted that if they didn't, these ecclesiastical communities would not endure to the next century.

Jessica's parents both worked a variety of jobs and couldn't take their kids to church regularly. As her padrino, I sincerely believed that it was the godparents’ task to step in. I thought Rosie and I could alternate taking the children (Jessica and her two brothers) on Sundays to a Roman Catholic Mass with an Episcopal Eucharist. As it turned out, the opposite happened: the kids would come with me, since I was responsible for the Spanish service—but the kids' Spanish was weak, so they would often continue on to Sunday school with the other children.

All in all, being a godparent was a wonderful experience for me. The kids got a Christian foundation--even though they no longer go to church, and the elder brother has become a messianic Jew! And I am still very good friends with their parents, mis compadres.

“SHARE8” (2011) fractal art by Robert D. Ogden

Models and dynamical systems

descriptions using mathematical concepts and language of a system; systems in which a function describes the time dependence of a point in a geometrical space

In the early years of this century, my Diocese decided it didn't want to have a separate Hispanic ministry (although it certainly intended to minister to this demographic). In my opinion, there were good and bad aspects of this decision.

The diocesan Hispanic establishment was out of touch with the masses and had grandiose ideas, sometimes inspired by Liberation theology (good) but taken out of the context of Latin America and inappropriate to South Texas reality. The Spanish translation of the Prayer Book, for instance, was in a Castellano (hermoso, especially the Psalms) that was unfamiliar to the Mexicanos y Tejanos (the translators were said to be Cuban ecclesiastics in exile).

While many Anglos in the Episcopal Church seemed to think that the language disconnect was the main obstacle to Hispanic recruitment (though this was not completely true for, say, Tejanos in central Texas). But I suspect the problem was that they wanted to find Hispanics modelled after themselves (or how they imagined themselves): “stable” families, professional jobs, highly literate; people who perhaps were unhappy with the Roman Catholic church for various reasons (including the prohibition of clerical marriage and rules on divorce), who would make a financial pledge, and who would be good churchmen and women.

Although the Episcopal Church was welcoming to Hispanics, it did not know how to address their spiritual needs—a need much more complex to address than any problem of language. I felt the Episcopal Church had a lot to offer to the community, including a spirituality less focused on personal sin and faults, and what needed balm the most. Simply repeating “God loves you” or “Dios vos quiere” is not enough.

At the time, I would have gladly yielded to anyone else who wanted to lead the Hispanic ministry in my parish. It is, after all, the women in my life—mother, sister, wives, lovers, daughters, goddaughter, friends, and madrinas—who made me the man I am. I often—too often—felt that God had chosen the wrong person for this task, and I constantly asked, “Why me?” The answer from our ‘loving, liberating, and life-giving’ God, of course, is, “Who else?” (“Be humble, Roberto, and accept the uncertainties of real life!”) So I did the best I could, trying to be faithful, and accepting the vagrancies of ‘real life.’

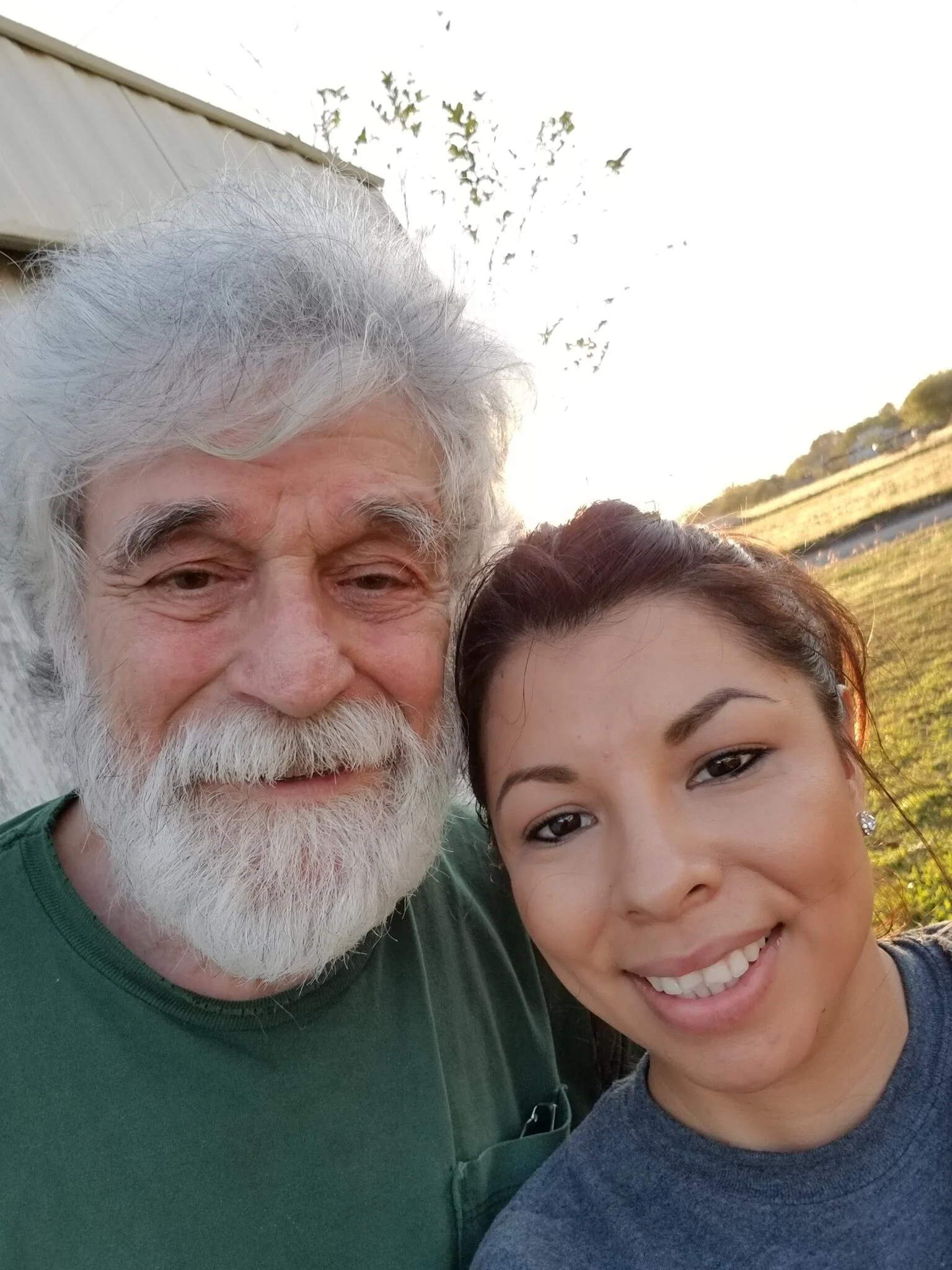

Goddaughter “Jessica” and me a couple of years back.

Even in my uncertainties with Hispanic ministry, there are knowns: I am proud of my goddaughter. Jessica is a cheerleader. Oh, she works in real estate now, but she was a cheerleader in high school and later even did a professional stint for the San Antonio Spurs. But beyond that, I mean she cheers people on, encouraging them not to give up. When her father, mi compadre, was diagnosed with stage-four lung cancer, Jessica encouraged him to hacer la lucha pa' vivir. And besides cheering him on to struggle for life, she took over his meds and went with him to the doctors, making sure he understood them. She also got him to change his habits, including to moderate his drinking. He had not been the best father when she was a girl, but she has forgiven him, although not forgotten a thing. In fact, with her brothers, father, uncles, and partner, Jessica is very sharp-tongued—quite a scold, they say. But towards me, her padrino, she is still muy respetuosa, and avoids disagreements. She knows, for example, that I would disapprove about her being against getting the COVID vaccine, something that I hear second-hand from her father. (“Unforeseen inputs constantly surprise you, Roberto!”).

Nevertheless, when I zoom in and see the example of mi ahijada Jessica, siento que de veras valía la pena.

Dr. Robert (Roberto) David Ogden is Associate Professor Emeritus of Computer Science at Texas State University in San Marcos, where he has lived since 1981. Originally from Dallas, Texas, he spent most of his professional life in the mathematical and computational sciences, working as a professor and programmer. In the 1970s, he took a year leave from DePaul University to teach physics at Rafael Cancel Miranda High School, a private school organized mainly by Puerto Ricans frustrated with the Chicago public-school system. Dr. Ogden also spent years working in Mexico at la Unidad de Ciencias Marinas in Ensenada, Baja California. After rejoining the Episcopal Church of his teen years, he served in Hispanic ministry at St. Mark’s in San Marcos, TX. Dr. Ogden is licensed as a Lay Minister, Lector, and Catechist in the Episcopal Diocese of West Texas, and he has online credentials to officiate at marriages. Since retirement, Dr. Ogden has played in a rock band, worked on his writing, and spent time with nieces and nephews—and now their children. In their old age, he and Rosie, his wife of 38 years, spend quality time caring for one another. They have two daughters, Miletus and Martha.